HOUSES OF MERCY IN THE WEST INDIES

In spite of the turmoil caused by conflicting monarchs claiming lands, and Spanish looting for gold and silver, and the plantation barons harvesting sugar and making rum, religious freedom was the undertone of normal society of the West Indies, and the Houses of Mercy, the Leprosariums, were no exception.

|

Leprosy seems to be a very ancient disease. The 13th

chapter of the Book of Leviticus treats of the Law

concerning leprosy in men and garments, and the 14th

chapter, of the rites of sacrifice in cleansing St. Lazarus, by which he renews all the privileges and all the gifts that his predecessors had granted to it and gives it fresh ones.

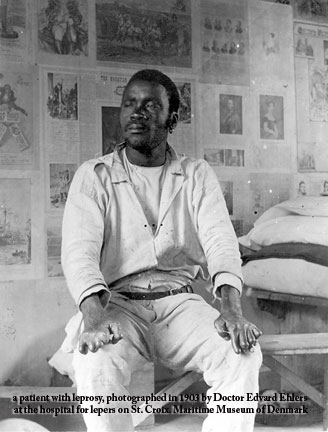

." An authentic representation of the leprosy in the Middle Ages exists in a picture at Munich by Holbein, painted at Augsburg in 1516 : St. Elizabeth gives bread and wine to a prostrate group of lepers, includ- ing a bearded man whose face is covered with large round reddish knobs, an old woman whose arm is covered with brown blotches, the leg swathed in bandages through which matter oozes, the bare knee also marked with discolored spots and on the head a white rag or plaster, and thirdlv, a young man whose neck and face are spotted with brown patches of vari- ous sizes. Virchow thinks that the painter had made a study of lepers from the leper houses. |

In Christian times the canons of the early councils (Ancyra, 314), the regulations of the popes (e.g., the famous letter of Gregory II to St. Boniface), the laws enacted by the Lombard King Rothar (seventh century), by Pepin and Charlemagne (eighth century), the erection of leper-houses at Verdun, Metz, Maestricht (seventh century), St. Gall (eighth century), and Canterbury (1096) bear witness to the existence of the disease in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. The invasions of the Arabs and, later on, the Crusades greatly aggravated the scourge, which spared no station in life and attacked even royal families. Lepers were then subjected to most stringent regulations. They were excluded from the church by a funeral Mass and a symbolic burial (Martène, "De Rit. ant., " III, x). In every important community asylums, mostly dedicated to and/or built by the Order of St. Lazarus and attended by religious, were erected for the unfortunate victims. The Caribbean was no exception.

Matthew Paris (1197-1259) roughly estimated the number of these leper-houses in Europe at 19,000, France alone having about 2000, and England over a hundred. Such lepers as were not confined within these asylums had to wear a special garb, and carry "a wooden clapper to give warning of their approach. They were forbidden to enter inns, churches, mills, or bakehouses, to touch healthy persons or eat with them, to wash in the streams, or to walk in narrow footpaths" (Creighton). (See below: IV. Leprosy in the Middle Ages.) Owing to strict legislation, leprosy gradually disappeared, so that at the close of the seventeenth century it had become rare except in some few localities. At the same time it began to spread in the colonies of America, the West Indies, and the islands of Oceanica. "It is endemic in Northern and Eastern Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, Persia, India, China and Japan, Russia, Norway and Sweden, Italy, Greece, France, Spain, in the islands of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

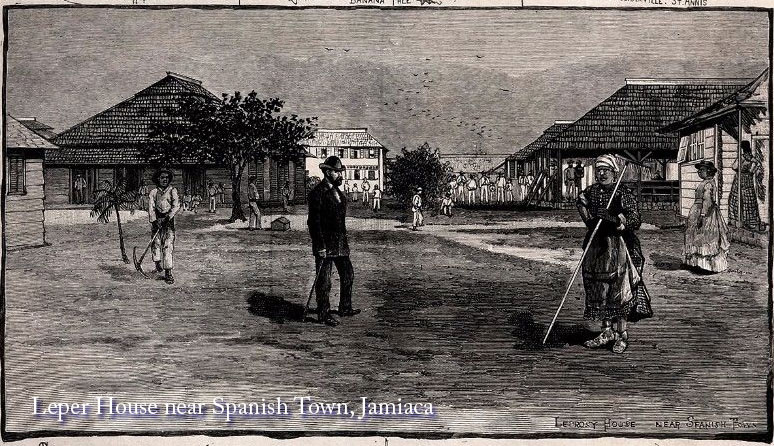

Almost every island in the Caribbean had a leprosarium, leper house, lazaretto or lazar house:

|

• Barbados, leprosy colony outside Bridgetown • Cuba • Guadeloupe and Martinique isolated their lepers on the island La Désirade, Trinidad on a small island named Chacachacare. • St. Kitts had a leper home at Sandy Point. Barbados had a lazaretto located three miles north of Bridgetown. • St Lucia had the Leper Home “Malgretoute”, two miles from Soufriere. • Antigua had a colony on “Rat Island” in St John’s Harbour. • Jamaica had colonies near old Spanish Town and Montego Bay • Puerto Rico, at the leper colony on Cabras Island • Trinidad, the Chacachacare Leprosarium • Virgin Islands: It is not known when leprosy first appeared but beginning around 1810, there was a desire for a special hospital for the lepers on St. Croix. But the first “leprosarium” is known from St. Thomas. It was on the peninsula Hassel Island and was in use 1833-1861. It was a very small, poorly-maintained and isolated hospital with about 10-20 regular residents. Subsequently, the lepers were transferred to a specially isolated building at the new municipal hospital in Charlotte Amalie. |

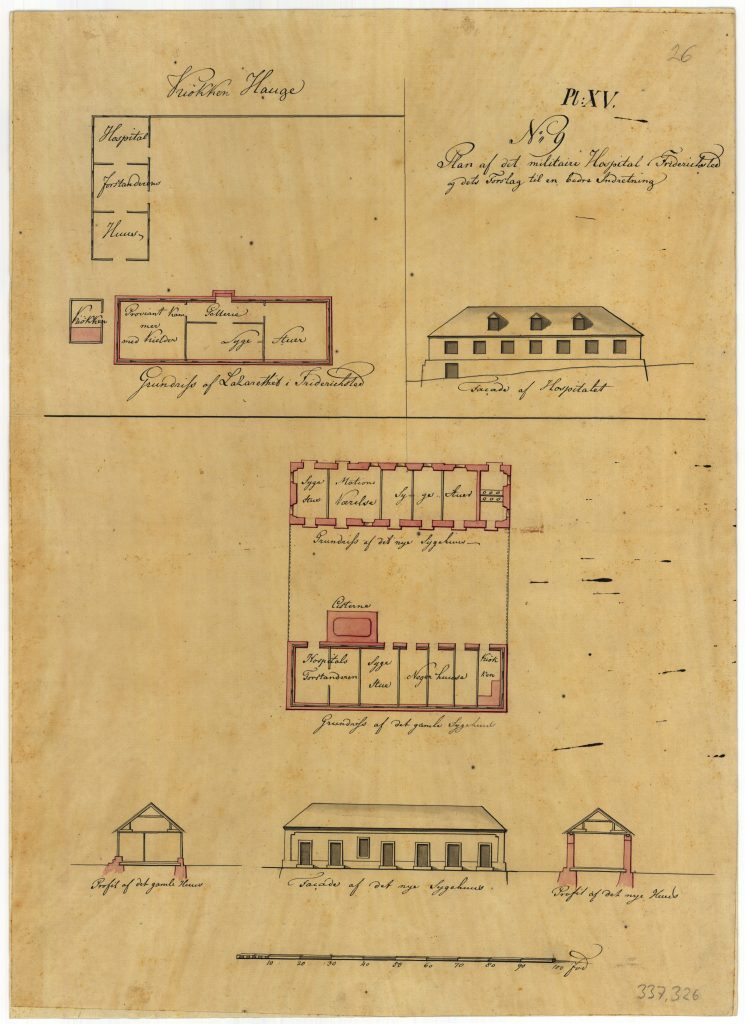

The military hospital in Frederiksted, c. 1778, drawn by Peter Lotharius Oxholm. Danish National Archives. |

Reported by R. G. COCHRANE in Leprosy in the

West Indies (Leprosy Review).

THE tour which was made recently through the West Indies

revealed one or two most interesting facts. The two chief

points which might be referred to briefly in passing, are

firstly that the incidence of leprosy seems to go pari passu

with the economic condition of the country and, secondly, from

superficial observation, there seemed to be a racial factor

influencing the type of disease seen in individuals. . For

instance, in Trinidad, where the East Indian population has

been domiciled from the time of the repeal of the Slavery Act,

Dr. Urich, the Medical Superintendent of the Chacachacare

Leprosy Settlement, pointed out that the Indian almost

invariably acquired a type of the disease which was different

from the African, and, generally speaking, the negroid races

showed much more severe cutaneous manifestations than the

Indians.

To show how acute a problem leprosy had become, let me quote from William TEBB’s “LEPROSY AND VACCINATION” published in London in 1893:

“During my visits to the Leeward and Windward Islands, 1888-89, I had the opportunity of conversing with residents,… and the general opinion was that leprosy was largely on the increase. In some islands, such as Jamaica, St. Kitts, and Trinidad, there are leper communities, which are gradually increasing; and appeals are frequently made in the Colonial Press for their segregation …”

On the 22nd January, 1889, I visited the lazaretto at Barbados, a crowded institution. A new ward was in course of construction… but the applications from the single parish of St. Michael were greater than the extra beds to be provided. .. the present system [is] of voluntary segregation. If the segregation were compulsory, as some now demand, the alarming spread of the disease, would be more fully exhibited.

The Asylum ( in Trinidad), which I visited in February, 1889, contained at that time 180 patients , who are admirably cared for by the French Dominican Sisters. Every bed is occupied.

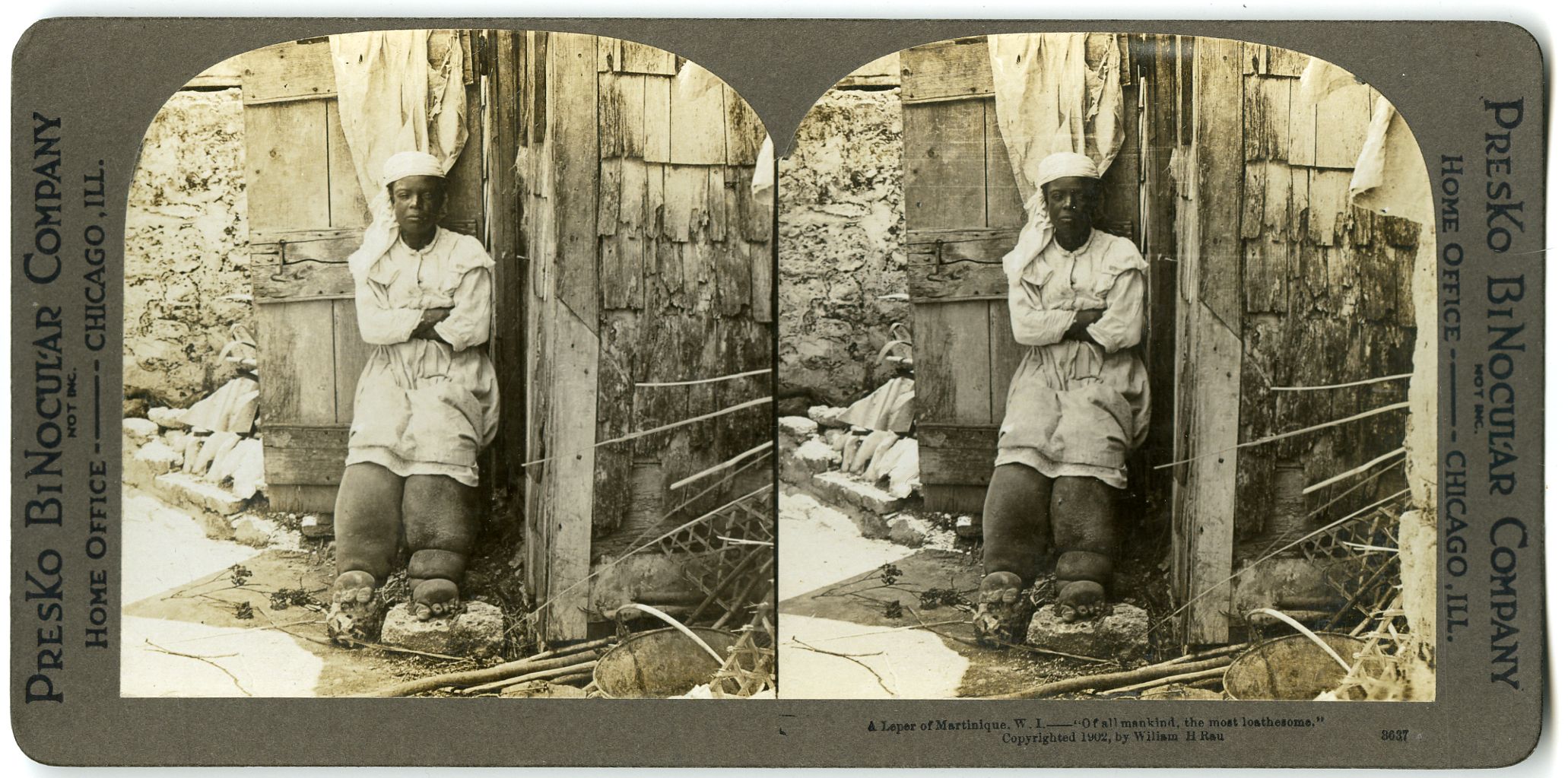

A Leper Colony of Martinque (1902)

• In the St. Christopher Gazette (of St. Kitts), the 17th May, 1889, entitled, “The most pressing question in the Colony”, the writer quotes Dr. Boon’s last report, which “clearly and forcibly showed the Government the enormous increase in our leper population during the last six years.”

In the Lazaretto, No. 11, a paper published in the West Indies, the editor asserts that a careful census carried out by medical officers would demonstrate that St. Kitts and Nevis contain more lepers per thousand of the population than any other British possession. To accommodate the growing community of lepers, a large lazaretto has recently been built at Sandy Point, ten miles from Basse Terre, St. Kitts, which already contains eighty inmates.

One thing is very noticeable in Nevis, namely, the way in which the leprosy spreads in each neighbourhood from single cases. It is not easily traced in St. Kitts, as the people there do not own land like the Nevis people, and are consequently more nomadic. One thing has struck me very much, and that is the number of shop-keepers that have contracted the disease.”

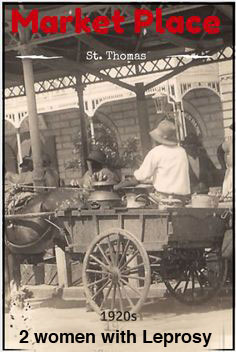

“We have also received a-letter from Dr. Boon, who says:—‘Leprosy has attacked people of all conditions in the West Indies. A few years ago a newly-appointed inspector of police enforced the local ‘Vagrant Act,’ and prevented the squads of mendicant lepers from perambulating the town, begging from house to house, and [troubling] people in the streets.

We count among our lepers (other than mendicants) bakers, butchers, salesmen in groceries and provision shops, fishermen, printers, editors, shopkeepers, planters, agricultural labourers, and carpenters.

In a lodging-house kept by a leper, members of the Bar lodged when on circuit, and slept on the same bed used by the leper when he had no lodgers.

Another leper kept a crèche, and tended about 20 infants at a tithe in his room for over ten years.”

In the report of the Blue Book of St. Vincent, British West Indies, 1890, the Administrator observes: — “It is greatly feared that leprosy, which has already proved so great a scourge to some of our colonial possessions, will become a serious trouble in St. Vincent."

It is clear from the quotations, anno 1889, that the terrible sickness, leprosy, was causing great alarm in the West Indian populations.

In “A VOICE OF THE WEST INDIES” published by John Horsford in 1856 , we read that “ persons afflicted with leprosy in its most loathsome form were seen in the street and alleys, soliciting pity and relief, and producing a sickening influence upon passers-by…”

“All lepers are shut up, without distinction of sex, rank, or age, in a hospital.., which is built outside the city” THE PRESENT STATE OF THE WEST INDIES published in 1778 by R. Baldwin.

• Dominica was the exception.

“leprosy has always been rare in Dominica and prior to the present century [=20th century] patients, usually not more than one case per year, were not isolated as the physicians were sceptical that the disease was transmitted by contact” wrote David Clyde in “TWO CENTURIES OF HEALTH CARE IN DOMINICA” (1980).

|

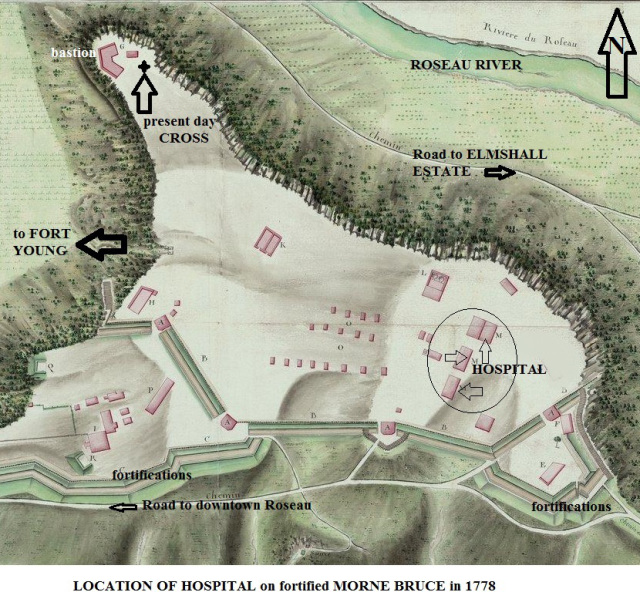

Dr. William Birge MD who published an eyewitness account of the presence of lepers in the hospital on Morne Bruce. He wrote “There is an excellent hospital situated on Morne Bruce, about two miles from the city, where the poor of the island receive treatment free.” The hospital started as a soldiers’ hospital in the 18th century as on a French map of Morne Bruce dated 1778, we find 4 buildings marked as “HOSPITAL” among the fortifications on Morne Bruce. In the year 1866, we read in a report on Her British Majesty’s colony Dominica : “ the poor house is situated on Morne Bruce .. The buildings of which it consists were formerly the soldier’s barracks…The number of inmates is 172 for the year.. A lunatic Asylum is affiliated to the poorhouse establishment .” This was not to be confused with a privately owned infirmary at Roseau and the Female Orphan Asylum run by the Religious Sisters. This hospital at Morne Bruce gradually turned into a poor house as all the beds over time became filled with cases of “old age, feeble paupers and incurable sick”. As Dr. Nicholls stated much later: “These wretched people cannot be turned out, for they have no homes, and no relations able and willing to care for them, and were they to be forced to leave the shelter of the hospital they would lie about the streets of Roseau thereby creating a public scandal...” “TWO CENTURIES OF HEALTH CARE IN DOMINICA” The hospital was permanently overcrowded. “The only establishment in the colony for the relief of the poor appears to be a hospital or poor-house.” stated a colonial report in the 1860’s . This hospital/poor house was closed in 1897. |

The DOMINICA CHRONICLE of March 12, 1938 described Dominica’s first leper colony: “The colony is made up of about 20 small houses perched jauntily on the somewhat barren slopes above the road. There is a gate-keeper’s house, a matron’s house, a hospital, a kitchen, servants’ quarters and the inmates’ homes. Each home is built to house two inmates in separate compartments. The colony is 200 acres in extent and there is consequently enough space to extend it at a later date if necessary.”

The article noted the presence of Bishop of Roseau, James Moris, together with the chaplain of the Leper Home, Rev. Father Felix Bogaert C.Ss.R. , Parish priest of St. Joseph. On that occasion the Administrator of Dominica, James Scott Neill, thanked the Catholic Bishop for his interest and work in the social improvement of the people of Dominica. He expressed the hope that Catholic religious Sisters would come to the Dominica to work in the leper Home.

in the book “THE CURIOSITIES OF FOOD “ by Peter Simmonds published in 1859 we read “The flesh of snakes is eaten by many in Dominica, particularly by the French, some of whom are very fond of it; but it is reckoned unwholesome, and to cause leprosy”.

“Although the white people in the West Indies are not exempted from Leprosy; the negroes are more subject thereto”…..” the children of infected parents are not always siezed with the leprosy and I have known the wives of the Leprous remain free from it for years.. This disorder frequently arises from being over-heated, and getting too suddenly cool. It however often breaks out without any visible cause” AN ESSAY ON THE MORE COMMON WEST INDIA DISEASES; AND THE REMEDIES WHICH THE COUNTRY ITSELF PRODUCES …BY A PHYSICIAN IN THE WEST INDIES” published in 1764 by T. Becket and P .A. de Hondt.

The Cure for Leprosy

Physicians Becket and de Hondt were optimistic that a cure could be found right here in the islands as they wrote; “I am notwithstanding persuaded, that the antidote of the Leprosy is to be found in the West-Indies”.

Dr. Clarke in Dominica brewed “a most powerful and successful remedy” which he claimed “an almost certain cure against leprosy” as we can read in a letter of T.M. Caton dated Feb 23, 1809 in the LONDON MEDICAL AND SURGICAL SPECTATOR. The wonder cure contained acid of arsenic, “ filtered, crystallied and pulverised” and the dose given to the patient was gradually increased. While all these opinions and effrots were propagated, doctors in Europe were getting closer to the cause of leprosy and the conditions conducive to the sickness . In West Europe leprosy had disappeared since the 16th century, but in Northern Europe, notable Norway, there were more than 2000 lepers in the period 1857-1864. Doctor Danielssen at Bergen found that bad food, clothing and lodging tended to increase leprosy. He also concluded that the disease was “neither infectious nor contagious”.

Danielssen’s collegue Dr. Gerhard Hansen identified in 1873 the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae as the causative agent for leprosy. The medical experts knew from that moment that leprosy had an identifiable cause.

In a communication read to the National Academy of Medicine of Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, on November 25th, 1937, A. OZORIO DE ALMEIDA and EDUARDO RABELLO reportd the positively favourable effect of oxygen and methylene blue under high pressure on Leprosy. At the request of the Dermatological Society, their paper was read before the Society on December 6th, with photographic documents in supoort of the results claimed.

But the inhuman treatment of lepers went on unabated in the colonies :

“The present social position of the poor mendicant leper .. is a most deplorable one, and it is not surprising that he is often subject to the most inhuman treatment. In the recent Report on Leprosy prepared by the College of Physicians, great prominence was given to the cruel neglect of the leprous outcast, and the necessity and humanity of decently lodging and housing him instead of allowing him to live on more like a wild beast than a human being.” found in THE LANCET, a British medical publication. The authors proposed that the British Government set up “suitable lazaretto” or leper houses.

While these humane considerations were expressed, the economic arguments in favour of expulsion and isolation of lepers was a more powerful argument for the colonial governments as colonies served only to make the homeland richer and powerful. Let us take Suriname, part of the Dutch Empire, as an example:

“Leprosy … could be harmful to an already weakening plantation economy. This concern prompted the local administration to develop a rigorous policy of strict isolation of leprosy sufferers.

This, in turn, intersected with a changing insight in Europe – including the Netherlands – that leprosy was non-contagious.

However, ‘in splendid isolation’ in the economically and politically marginal colony Suriname, Dutch physicians like Charles Landré and his son, could afford to ignore the European non-contagious approach and continue to support the strict isolation policies.” VRIJE UNIVERSITY Amsterdam

In 1867 the Royal College of Physicians in London published a comprehensive “REPORT ON LEPROSY ” which concluded that leprosy was not contagious and hereditary. The research was based on data from all around the British Empire and the findings of Dr. Danielssen and Boeck published in Norway 20 years earlier.

In 1868, THE LANCET and THE MEDICAL TIMES AND GAZETTE published some of the main findings :

• The distinctive character of leprosy are the same in all

parts of the world.

• There are two forms of the disease, tuberculous and

anaesthetic.

• The term “leprous” might be wrongly applied to other chronic

maladies of the skin occurring in unhealthy persons who live

in poverty and neglect cleanliness.

• The improvement in diet “is one of the principal factors of

the gradual decline “ and disappearance of leprosy in Europe.

• The extent to which leprosy prevails in many colonies of the

British Empire, and the inevitable destitution and mendicancy

among the population, make this investigation a matter of

“special duty” for the British government. (In other words, it

was a huge problem in the colonies and had economic

repercussions.)

• Leprosy appears to be on the increase in some of the West

India islands, notably Jamaica.

• The provisions made for lepers in the colonies are poor;

leper houses are often “ dreary, filthy, dilapidated hovels”.

Although the report was based on more than 250 “returns” or reports submitted by medical authorities from British colonies, there was a lot of scepticism in the same colonies about the findings in this report. Especially the conclusion that Leprosy is non- contagious, non-communicable by proximity or contact with the disease and that therefore isolation or segregation was unnecessary. Indeed why did Father Damien, from Belgium where the sickness was not present since centuries, contract and die from Leprosy, after only 16 years living among and ministering to the lepers of Molokai ?

In 1873, just 5 years after the publication of this British Report, Dr. Gerhard Hansen in Norway discovered bacteria in leprosy lesions and identified the bacterium. He therefore proved that Leprosy was an infectious disease caused by bacteria and that it was not hereditary. Two of the key conclusions statements in the 1867 REPORT ON LEPROSY of the Royal College of Physicians were completely wrong but were nevertheless promoted by the Colonial Office as the Gospel truth for decades.

Dr. Gavin Milroy, the principal writer of the 1867 REPORT on LEPROSY, visited the West Indies from September 1871 onwards as there was a strong rumour in Trinidad that a cure against Leprosy was found. This proved to be wrong also. As he visited Guyana, Trinidad, Barbados, Antigua and Dominica, Dr. Milroy found out, to his great dismay, that the 1867 Report was almost unknown in the islands. He also found “ superstitious horror of the disease” in the islands.

“Dr. Milroy’s task now became one of spreading the word according to the College of Physicians to a superstitious and incredulous colonial world. Throughout his tour he drummed home the message that leprosy was hereditary and not contagious, and therefore strict isolation was unwarranted and the neglect of patients inhumane” quoted from LEPROSY AND EMPIRE by Rod Edmond published in 2006.

However the old ways in the West Indian islands continued and the leprosy situation got worse in Dominica as the island entered the 20th century.

Just before the turn of the century, in 1897, the Morne Bruce Poor House filled with lepers, incurables and “lunatics” was closed. No other provision was made for the special accommodation of infirm paupers until 1923. according to “TWO CENTURIES OF HEALTH CARE IN DOMINICA” by David Clyde (1980).

Leprosy Continues Today

Leprosy has not been eradicated and World Leprosy Day is observed each year at the end of January to remind us . These days it is called “Hansen’s disease”, a new name that does not carry the terrible connotations and stigma which existed since biblical times. Although 95% percent of the world population is immune to Leprosy, new cases keep appearing in certain countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that “ at the beginning of 2010, the registered prevalence of leprosy in the world was 211,903 cases, and 244,796 new cases were detected during 2009, as reported by 141 countries” , the United States among others.

In June 2013, genetic research, published in the journal SCIENCE, proved that the leprosy causing bacterium Mycobacterium Leprae, extracted from graves from the Middle Ages in Europe ( = the period between the fall of Rome in 476 CE and the early 1500) is almost identical to the bacterium which causes leprosy in the world today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Their plight

was actually worse than |

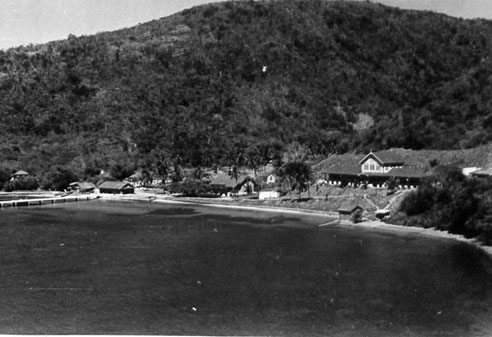

1944. Trinidad and Tobago. Sky View Leper Colony

Copyright 2017. The Sacred Medical Order - Knights of HOPE (SMOKH since 2006) • Worldwide

Privacy Policy | Terms

of Use | Updated on Nov. 21, 2017